Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company

Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company courtesy of Scripophily.com

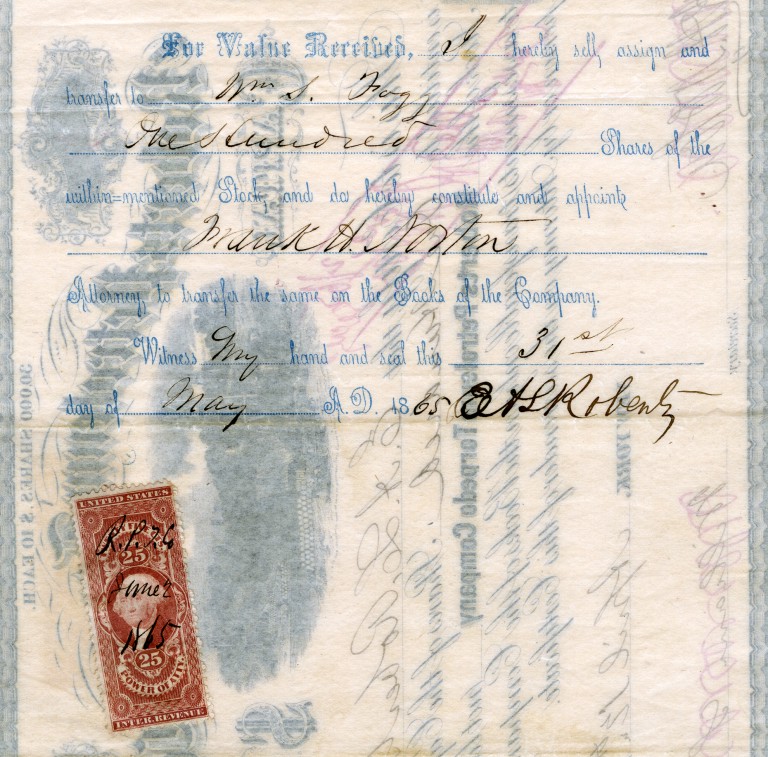

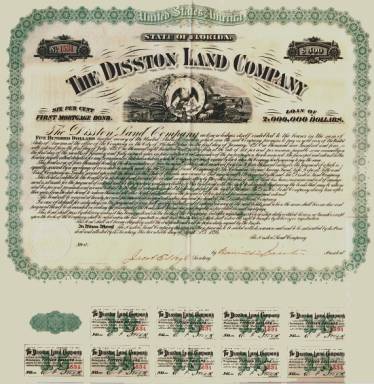

Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company Stock Certificate signed by Edward A. L. Roberts – RARE (Only 3 known signed by Roberts) Roberts’ “Exploding Torpedo” was the birth of modern-day shale fracking – Issued April 12, 1865 (Day of Robert E. Lee’s Surrender at Appomattox Court House)

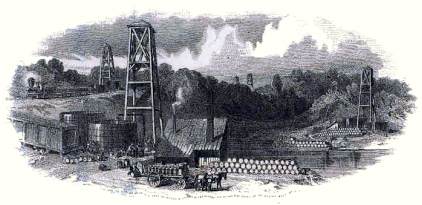

Certificate from the Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company issued in 1865. This historic document has an ornate border around it with vignettes of an oil filed and the torpedo exploding. This item is hand signed by the company’s president, William S. Fogg and secretary, and is over 151 years old. Civil War Tax Stamp attached to face of stock. This RARE certificate was issued to and endorsed on the back by the company founder, Edward A. L. Roberts (There only three known certificate signed by Edward A. L. Roberts ).

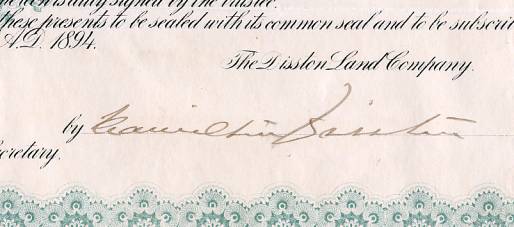

Roberts’ signature on back of certificate

Certificate Vignette #1

Certificate Vignette #2

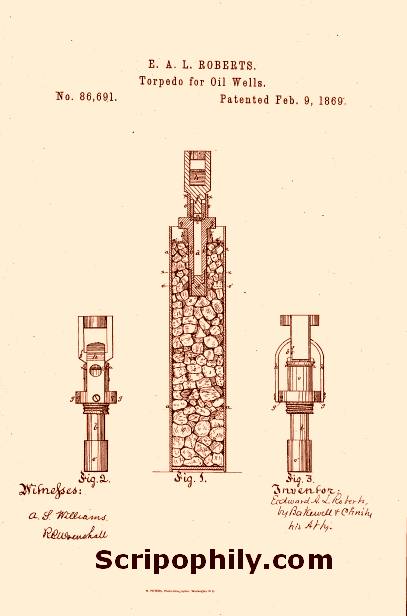

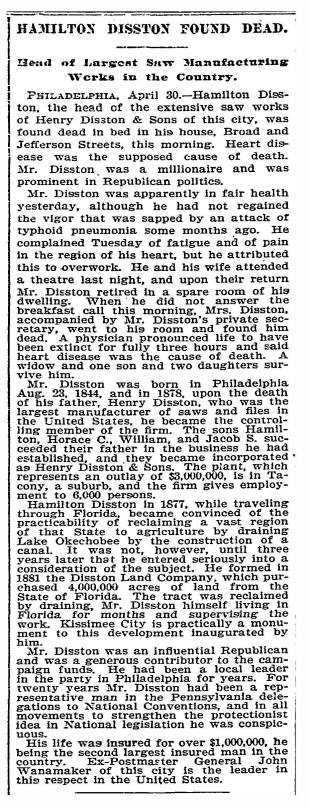

Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Patent –

(Shown for Illustrative Purposes)

Edward A. L. Roberts developed the first torpedo and submitted a patent application in November 1864. Roberts, an American Civil War veteran, came up with the concept of using water to “tamp” the resulting explosion, after watching Confederate artillery rounds explode in a canal at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Roberts developed his first torpedoes in 1865 and 1866. In November 1866 he was granted a patent on his torpedo application, and founded the Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company. William Reed also developed a torpedo design and went on to found a rival company “for the purpose of infringing and breaking down the Roberts patent. Roberts charged $100-200 per torpedo as well as a royalty amounting to 1⁄15 of the increased oil production. To avoid paying the exorbitant fees, an owner of a well would often hire men who illegally produced their own torpedoes and used them at night—the practice giving rise to term “moonlighting”. Roberts spent $250,000 to protect his patent from the “moonlighters” by hiring the Pinkerton National Detective Agency and filing numerous lawsuits. Roberts’ torpedo patents expired in 1879.

Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company – Background

Prior to the invention of the oil well torpedo, oil wells produced only small quantities of oil for a short time. They had to be redrilled due to the build-up of paraffin and clay deposits. It was not until January 28, 1865 when Col. E.A.L. Roberts successfully discharged his eight pound torpedo, that oil production could be increased significantly. The torpedoes, which were lowered into the drilled wells, were filled with gunpowder, and ignited by a weight dropped along a suspension wire onto percussion caps in the torpedo. In later models, the gunpowder was replaced by nitroglycerin. Oil well production increased over 40 fold as a result of Roberts’ invention. Modern torpedoes are still used today. In February, 1865 E.A.L. Roberts and his brother Walter formed the Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company. Roberts was granted a patent that gave his company a virtual monopoly on all types of torpedo used in the oil industry. This patent was vigorously fought by both oil exploration companies and other would-be torpedo producers. In August 1866, the United States Supreme Court confirmed the Roberts’ sole right to the patent. (Source: The Early Days of Petroleum, Theodore B. Robinson, Journal of the International Bond & Share Society, November 1997).

The material below is being used with the permission of AnaLog Services, Inc. and The Otto Cupler Torpedo Co. and was obtained from the website www.logwell.com.

In Northwestern Pennsylvania there flows a stream called Oil Creek. Along the banks of Oil Creek have been written some of the most thrilling and romantic chapters in oil field history. It was near this stream, on August 27, 1859, that Col. Edwin L. Drake completed the first well drilled specifically for oil. And it was there, on January 21, 1865, that Col. E.A.L. Roberts made the first successful oil well shot on the Ladies Well, using 8 pounds of black powder (nitroglycerin was first used 2 years later), ushering in the era of “Oil Well Shooting”, and in no small measure saving the Pennsylvania oil industry.

In 1846, Ascanio (Ascagne) Sobrero, then a pupil of Pelouze, the eminent French chemist, hit upon Nitroglycerin by mixing fuming nitric acid, sulphuric acid, and glycerin in the proper proportions. Ascanio didn’t know it was loaded, for he subsequently blew the lab to splinters, narrowly escaping death himself. Glycerin by itself is a harmless substance, and so it is all the more surprising when under the influence of two acids, it becomes one of the most powerful explosives ever known to man. McLaurin described nitroglycerin as follows: “A flame or a spark would not explode Nitro-Glycerine readily, but the chap who struck it a hard rap might as well avoid trouble among his heirs by having had his will written and a cigar-box ordered to hold such fragments as his weeping relatives could pick from the surrounding district.”

In those early years, nitroglycerin had an adverse effect even upon man’s basic nature, as McLaurin described life in the oil regions of Pennsylvania, “The Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Co. was organized in New York to construct torpedoes and carry on the business extensively. Oil men were rather skeptical as to the advantages of the Roberts method, fearing the missiles would shatter the rock and destroy the wells. The Woodin well, a dry-hole on the Blood farm, received two shots and pumped eighty barrels a day in December of 1866.

During 1867 the demand increased largely and many suits for infringements were entered. Roberts seemed to have the courts on his side and he obtained injunctions against the Reed Torpedo Company and James Dickey for alleged infringements. Justices Strong and McKennan decided against Dickey in 1871. Oil Producers subscribed fifty thousand dollars to break down the Roberts patent and confidently expected a favorable issue. Judge Grier, of Philadelphia, mulcted the Reed Company in heavy damages. Nickerson and Hamar, ingenious, clever fellows, fared similarly. Roberts substituted Nitro-Glycerine for gunpowder in 1867 and established a manufactory of the explosive near Titusville.

The torpedo-war became general, determined, and uncompromising. The Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Co. charged exorbitant prices, two hundred dollars for a medium shot, and an army of “moonlighters”, nervy men who put in torpedoes at night, sprang into existence. The “moonlighters” effected great improvements and first used the “go-devil drop weight” in the Butler, Pennsylvania field in 1876. The Roberts crowd hired a legion of spies to report operators who patronized the nocturnal well-shooters. The country swarmed with these emissaries. You couldn’t spit in the street or near a well after dark without danger of hitting one of the crew. Unexampled litigation followed. About two-thousand prosecutions were threatened, and most of them begun, against producers accused of violating the law by engaging “moonlighters”. The array of counsel was most imposing. It included Bakewell & Christy, of Pittsburgh, and George Harding, of Philadelphia, for the torpedo company. Kellar & Blake, of New York, and General Benjamin F. Butler were retained by a number of defendants. Most of the individual suits were settled, the annoyance of trying them in Pittsburgh, fees of lawyers and enormous costs inducing the operators to make such terms as they could. By this means the coffers of the company were filled to overflowing and the Roberts Brothers rolled up millions of dollars.”

As the litigation continued the devastating accidents began, “Nitroglycerine literally tears its victims into shreds. It is quick as lighting and can’t be dodged. The first fatality from its use in the oil regions befell William Munson, in the summer of 1867 [actually 1868] at Reno. He operated on Cherry Run, owning wells near the famous Reed and Wade. He was one of the earliest producers to use torpedoes and manufactured them under the Reed patent. A small building at the bend of the Allegheny below Reno served as his workshop and storehouse.

For months the new industry went along quietly, its projector prospering as the result of his enterprise. Entering the building one morning in August, he was seen no more. How it occurred none could tell, but a frightful explosion shivered the building, tore a hole in the ground, and annihilated Munson. Houses trembled to their foundations, dishes were thrown from the shelves, windows were shattered, and about Oil City the horrible shock drove people frantically into the streets. Not a trace of Munson’s premises remained, while fragments of flesh and bone strewn over acres of ground too plainly revealed the dreadful fate of the proprietor. The mangled bits were carefully gathered up, put in a small box, and sent to his former home in New York for interment. The tragedy aroused profound sympathy. Mentally, morally, and physically William Munson was a fine specimen of manhood, thoroughly upright and trustworthy. He lived at Franklin and belonged to the Methodist church. His widow and two daughters survived the fond husband and father. Mrs. Munson first moved to California, then returned eastward, and she is now practicing medicine at Toledo, Ohio, the home of her daughters, the younger of whom married Frank Gleason.”

The term “moonlighting” emerged from this struggle. Moonlighters mixed their batches of nitroglycerin in crude equipment by day and by the light of the moon strapped their cans of nitroglycerin over their shoulders and proceeded to their dangerous and illegal task of shooting wells. Anyone who has witnessed an open hole oil well shot can testify as to the tremendous height reached by the resultant water geyser or dust and rock cloud. This sign of a well being shot was watched for by the Pinkerton detectives who were hired by Roberts, and who had fanned out throughout the oil regions. Night would mask shooting activities to a degree, and thus was born the dangerous business of moonlighting. The Roberts patent expired in 1883 and Congress refused to renew it due to all the strife.

In 1884, The Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Co. changed its name to The Otto Cupler Torpedo Co., which company still operates to this day out of Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Below are some newspaper articles rergarding the company:

From The Titusville Morning Herald of June 17, 1866, “Our attention has been called to a series of experiments that have been made in the wells of various localities by Col. Roberts, with his newly patented torpedo. The results have in many cases been astonishing. The torpedo, which is an iron case, containing an amount of powder varying from fifteen to twenty pounds, is lowered into the well, down to the spot, as near as can be ascertained, where it is necessary to explode it. It is then exploded by means of a cap on the torpedo, connected with the top of the shell by a wire. The object of the torpedo is to clean out all the deposits at the bottom of the well such as gravel, pieces of seed-bag, etc., as well as to open the fissures, where the oil comes through. These frequently become perfectly clogged with paraffine, and other matter that effectually prevents the production of oil from the well. It is claimed that the explosion of the torpedo at so great a depth, cannot result in any serious damage to the well.

“A large number of wells have been experimented on, and the most signal success has attended the same. Several wells on the Tarr farm, on Oil creek, have proved the most productive as yet. One of these was increased in production by the use of the torpedo from ten to over one hundred barrels per day.

“Paraffine, one of the parts of petroleum, has a tendency to form in bottoms of all wells, more especially after they have been worked a short time. We have known numerous instances where the conducting pipes have become so clogged with it as to render working the well impossible, until the pipes were taken up and cleaned out. We have seen the paraffine taken these the full size of a two and a half inch pipe, of about the same consistency as lard. It is but reasonable to suppose that this substance accumulates at the bottom of the well or in oil fissures, and in a short time effectually stops them up. Production thus ceases, and the well is abandoned. By keeping these fissures rid of this impediment, it is hard to tell the vast amount of oil that could be brought to the surface that is now lost. We desire to call attention to the startling facts that appear in the testimonials published in our advertising columns by the Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company.

“The reliable source whence these certificates came seems to preclude the possibility that the torpedo is a high-blown humbug, besides it would seem to be the most consummate folly to publish statements whose falsity could be so readily exposed, as would be the case with these if they were untrue, and yet it is only the involuntary prompting of human nature, on hearing such remarkable assertions, to ask ‘really, are these things so?’

“If every unsuccessful well owner shall find an affirmative answer to this question, we know somebody who will make a good thing. And if we are correctly informed, the Colonel is deserving of the most perfect success; for notwithstanding the groundless claims of rival contestants, backed by money and talent and brazen impudence, he has carried his invention gloriously through upon its own merits, as is fully shown by the late decision of the Commissioner of Patents.

“If the torpedo shall do one-tenth as much for other territory as it seems to have done for the Tarr Farm, it will prove to be more of a substantial benefit to the oil regions than all other patent implements and machines that have ever been invented. It is worthy of the attention not only of all who are directly interested in the production of petroleum, but of all who desire the prosperity of this oil county to inquire into this matter.”

From The Titusville Morning Herald of July 2, 1866, “A gentleman who has just called on us from Tarr farm, tells us that an experiment was made on the 21st, with one of Roberts’ Torpedoes in the ‘Bakery Well’ which has formerly pumped from 7 to 8 barrels per day. The production has continually increased. On the 27th it produced 60 barrels and yesterday the production was 100 barrels. We wonder how the owners feel at the great difference in their balance sheet! To increase a production 1200 per cent in a week is no small gain. The ‘Hayes well’, Petroleum Centre, was ‘fired Off’ last Saturday the 13th, and it has greatly improved. The exact figures we have not got. The Roberts’ Torpedo must scatter the paraffines or break things generally.”

From The Titusville Morning Herald of February 8, 1867, “This company owns about twelve patents for exploding torpedoes, besides the patents of A. Nobel, for the exclusive right to use nitroglycerine in oil wells, for the purpose of increasing production by any known method of exploding torpedoes, or shells, under water. This effectually prohibits the use of any torpedo unless by a license from the Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company. The energy which this Company, with Colonel Roberts as its General Superintendent, has shown in introducing the torpedo for the production of oil, must commend itself to every oil producer in the oil regions. Although at first they met with strong opposition, and no one was willing to permit a torpedo to be used in their wells, still after much solicitation permission was given, and a dry hole was made to produce eighty barrels of oil per day.

“As soon as this was accomplished, a great demand sprung up for the torpedoes. Other parties came in to compete with the Colonel, and every exertion was made by others to prevent his patent from being issued for the application of the torpedo to oil wells, delaying its issue for more than two years. During this time many persons, acting upon the supposition that he would be defeated by the Patent Office, expended large sums to prepare themselves to operate oil well torpedoes. But the final success of Col. Roberts last November and the injoining of several of the infringers have convinced all parties that the Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company can and will sustain their patents.”

From The Titusville Morning Herald of June 10, 1868, “A terrible explosion took place in the well No. 25, Tallman Farm, Shamburg. The report was not so loud as that on Church Run, but the effect was equally satisfactory. Another testimony to the value of the Roberts torpedoes. Franklin W. Andrews is the fortunate owner of the well. Go and do likewise.”

From The Titusville Morning Herald of October 28, 1868 “It would be superfluous, at this late day, to speak of the merits of the Roberts Torpedo. From Tidioute to Scrubgrass, for the past three years, it has been a most successful operation, and has increased the production of oil in hundreds upon hundreds of oil wells to an extent which could hardly be overestimated. Next to the discovery of oil, no invention has done more to enrich well owners, than the Roberts Torpedo. Three years ago Col. Roberts finding that nitroglycerine was the most powerful explosive agent that could be employed in torpedoes, turned his attention to the manufacture of this compound, and established a factory near this city, under the direction of one of the most experienced chemists of this country, George Mowbray. But his enterprise was temporarily suspended as the article could be purchased much cheaper in the Eastern market.

“Of late, however, the source of supply has been cut off, owing the danger and insecurity attending its transportation and the Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company have again started a factory for the manufacture of nitroglycerine, upon an extensive scale, at a safe and convenient distance from the city. The best machinery, with all the latest improvements, by which the utmost safety is attained, is employed, and the manufacturing is conducted under the personal superintendency of Col. E.A.L. Roberts. On Friday last the new works were duly tested with the most satisfactory results; over a thousand pounds of acids and glycerine, a portion of which has already, at present writing, been exploded in oil wells. It is the intention of the Company to manufacture nitroglycerine for their own use exclusively, and in such quantities, as their orders may require. Their object is to have the article fresh when handled, thus diminishing the danger to agents and others from explosion.

“The Company deserves great credit for the energy displayed by them in the erection of their extensive Factory, so soon after it had been demonstrated that nitroglycerine could not be shipped with safety by rail. Ten days ago there was not a stick of timber on the ground; now the factory is complete in all its parts and appointments, and of sufficient size to make a thousand pounds of nitroglycerine per day. The Roberts Petroleum Torpedo Company believes, from their experience during the past three years, that within the next six months, no oil operator can be persuaded to use anything but nitroglycerine in old wells, and that with the facilities they now enjoy, they will be able to meet the growing demand upon them for nitroglycerine torpedoes in all parts of the oil region. We understand that it is the purpose of Col. Roberts in connection with other gentlemen owning the exclusive right to manufacture and fire nitroglycerine under Nobel’s Patent, to erect during the ensuing winter or early spring, an establishment for the manufacture of the same, on the Lake Shore, at some convenient point for the supplying of the mining districts of Lake Superior with nitroglycerine.”

From The Titusville Morning Herald of September 17, 1870, in an article discussing the completion of the Roberts & Company’s machine works, planing mill, and torpedo shop, a mention is made of a tin torpedo, “The shells are now manufactured of tin, instead of cast iron, the tin cylinder, which was formerly discarded for lack of strength, being now remedied by a stiff wire coil which enables it to resist any pressure.” No records have been found showing details of the construction described above; but, from the description, this is not the tin torpedo design that was soon to take over the industry.

The material above is being used with the permission of AnaLog Services, Inc. and The Otto Cupler Torpedo Co. and was obtained from the website www.logwell.com.

Copyright © 2000 The Otto Cupler Torpedo Co. & AnaLog Services, Inc.

$295.00 –

$295.00 –  $39.95 –

$39.95 –  $149.95 –

$149.95 –  $250.00 –

$250.00 –  $199.95 –

$199.95 –  $99.95 –

$99.95 –  $99.95 –

$99.95 –  $79.95 –

$79.95 –