Jacob Little – The Original Wall Street Bear by Bob Kerstein

Jacob Little

The Original Wall Street Bear

by Bob Kerstein, CEO Scripophily.com

|

Is Your Disney War Bond Genuine?

By Fred Fuld III at AntiqueStocks.com

Author of the book: Let Me Entertain You with Antique Stock Certificates

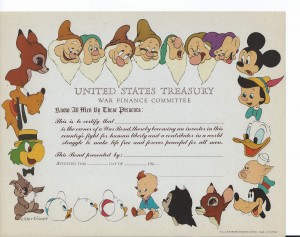

During World War II, the Disney company issued “War Bonds” which, although they were not true bonds themselves, were given to investors who bought U.S. Treasury War Bonds. The certificates feature 22 different Disney characters making up the border of the certificate, including Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, and Pluto. The Disney certificates were given out by banks and war finance committees. These are available in the collectors’ market in both issued and unissued form.

There were only two authorized printers: the U.S. Government Printing Office and the Homer H. Boelter Printing Company. (Check the lower right corner for the name of the printer.) There were also two different types of war bonds, one in multi-color and one in black and white, where dot and line patterns were used in place of colors. The black and white variety is extremely rare.

If you collect Disney War Bonds, be careful of color photocopy fakes that are being sold. There are several ways to check if a war bond is genuine or not:

1. For the certificates printed by the Government Printing Office, if you hold the paper up to the light, you will see that the paper has a watermark depicting an eagle, about three inches high by three inches wide. All Disney War Bonds printed by the U. S. Government Printing Office have an eagle water mark. If it says it is printed by the Government Printing Office and it doesn’t have an eagle watermark, it is a fake. Certificate printed by the Boelter company do not have an eagle watermark but they do have the watermark of the paper company that manufactured the paper.

2. The certificate has a very light beige color. If it has a yellow background, it is a color photocopy. Even if the paper was left in the sun for a long time, it would not have a yellow background, it would have a darker beige background.

3. Look very closely at the background of Donald Duck’s eyes. They are made up of very tiny light blue dots (use a magnifying glass if necessary). If the eyes are a solid dark blue or solid purple, the certificate is a photocopy fake.

STOCKS OF AMERICA’S PIONEERING TELECOMMUNICATIONS

Join our American Stock and Bond Collectors Association Group on Facebook

American Stock and Bond Collectors Association Group on Facebook

Join our American Stock and Bond Collectors Association Group on Facebook

See some our Facebook activity below:

[custom-facebook-feed]

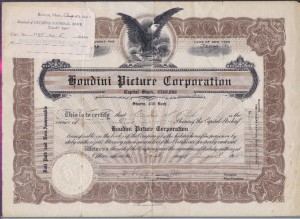

Houdini Picture Corporation By Fred Fuld III at AntiqueStocks.com

Houdini Picture Corporation

By Fred Fuld III at AntiqueStocks.com

Author of the book: Let Me Entertain You with Antique Stock Certificates

If you ask the average person on the street to name one magician, chances are that the most popular response is Houdini. Harry Houdini, who was born Erik Weisz, (his family later changed it to Ehrich Weiss), was from Budapest but moved to the United States when he was four years old, first to Wisconsin, then to New York City.

He eventually became one of the world’s most famous, if not the most famous, magician, escape artist, and illusionist, taking on the name Harry Houdini. However, what many people don’t know about Houdini is that he was also a motion picture producer, director, actor, screenwriter, and stuntman. His company was called the Houdini Picture Corporation. (See the image above.)

What is unusual about several of these certificates that have appeared in the collectors’ market is that Houdini’s signature is very light. This has led many to speculate that Houdini was using disappearing ink.

So what did this company actually do? It produced three silent black and white movies from 1921 to 1923:

The Soul of Bronze

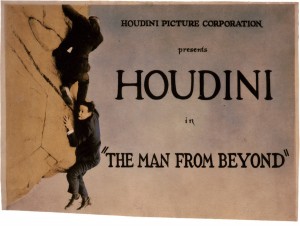

The Man From Beyond

Haldane of the Secret Service

The Soul of Bronze was actually a movie from France that Houdini reformatted and distributed, but did not star in. The Man From Beyond is a movie about a man (played by Houdini) who comes back to life after being frozen for 100 years in the arctic. Haldane (also played by Houdini of course) is about a Secret Service agent who goes after counterfeiters and tries to rescue a woman.

Not many people are aware that although Houdini was the president of the company, his brother Theodore Hardeen actually ran it. One of the investors in the company was Harry Keller, a popular magician in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s.

Houdini even appeared in a few other movies that he did not produce, including The Grim Game and Terror Island, both distributed by Paramount Pictures.

Houdini’s signature appears on one other stock certificate, Martinka & Company, the oldest magic company in the United States. The Society of American Magicians held their meetings in the back of the shop. Houdini was the owner in 1919. He used his formal signature to sign the certificates.

Historical Notes

Originally Published and Printed by G.Labarre, The LaBarre Newsletter, Issue 1, Winter 1981

Historical Notes

Stock and bond certificates and shares are more than mere representations of wealth or financial gain. More than that, they are reflections of human endeavor, industrial expansion and the growth of this nation. Each has its own unique and fascinating story to tell. With those important points in mind, it is both interesting and useful for collectors and investors to be aware of historical background of companies that have issued stocks or bonds to finance their development and growth. This first issue of the “Stock and Bond Investment Quarterly” will discuss a perennial favorite of many types of collectors; railroad companies.

Taunton Branch Railroad Company, Massachusetts

This company was incorporated in April 1835, to construct a railroad from Taunton to Mansfield on the Boston and Providence line. Construction began that year, and was completed in August 1836. On July 2, 1840, the New Bedford and Taunton Railroad was completed, and connected with the Taunton Branch. Both railroads operated under the same management.

The original issue of capital stock amounted to $250,000 for the Taunton Branch. Actual construction costs overran that amount slightly at about $256,000. The line was short, running just over eleven miles. The railroad began paying dividends three years after completion, and within six years was paying a tidy six percent return on investment, a rate it was able to maintain for a number of years.

Attica & Allegheny Railroad Company, New York

The Attica & Allegheny Valley Railroad was succeeded by the Arcade & Attica Railroad.

Unlike the Taunton Branch Railroad Company already discussed, this railroad seemed doomed from the outset. Incorporated in November 1852, only about twenty-five miles of track were graded between Attica and Arcade during 1853 and 1854. In February 1856, the railroad was sold upon foreclosure of its mortgage.

Fall River Railroad Company, Massachusetts

This particular railroad was formed by the consolidation of three separate lines: the Fall River Branch, the Middleboro, and the Randolph and Bridgewater Companies. The Fall River Branch was incorporated in March 1844, to construct a line from Fall River to Myrick’s Station. Both the Middleboro and the Randolph and Bridgewater Companies were formed in March 1845, the former to construct a railroad from Bridgewater to the Fall River Branch at Myrick’s Station, and the latter to build a line from Bridgewater to the Old Colony Railroad in Braintree. The three merged in August 1845, following the successful completion of their respective segments of the entire line. In April of the following year, the merger was granted official sanction by an act passed by the state legislature.

Share capital of the three companies totaled slightly over $1,000,000, a significant investment for that era. Construction of the entire line to its junction with the Old Colony was completed in December 1846. The entire line covered forty-two miles. Nearly a decade later in 1854, the Fall River and Old Colony Lines were consolidated, thus forming the Old Colony and Fall River Railroad.

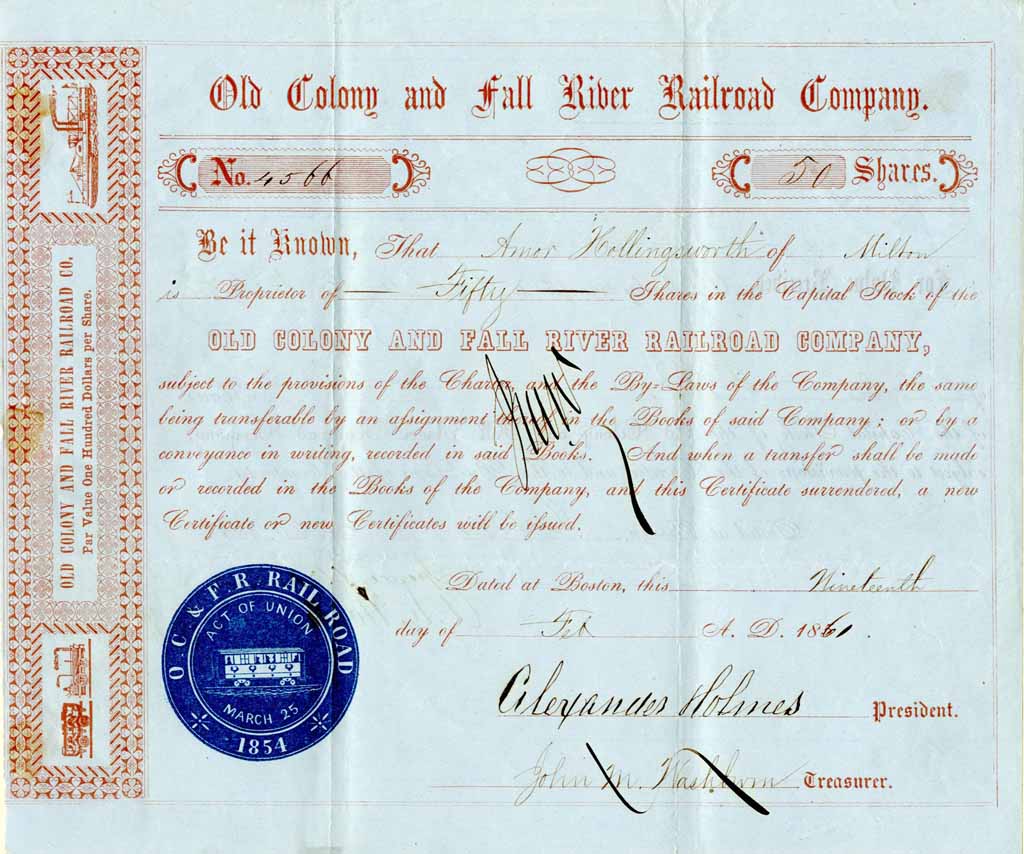

Old Colony and Fall River Railroad, Massachusetts

This merger was authorized on March 25, 1854. The total length of road operated by the company totaled about ninety miles.

One individual, Richard Borden, played an important role in the development of the Fall River Railroad and also the subsequent merger with the Old Colony. Born in 1795 in Fall River, Borden was one of the early industrialists of the area. Following the War of 1812, Borden became involved in shipbuilding, cotton milling, and ironworking, lucrative businesses, which expanded rapidly throughout the 1820’s and 1830’s. The Fall River Iron Works, in which he held a major interest, was created in 1821 with an initial capital investment of $18,000. By 1845, the business was worth almost one million dollars, and boasted an ironworks valued at half a million dollars.

Rapid, cheap transportation of materials and finished goods was naturally a source of considerable interest and concern to Borden. To that end, and mainly through his personal efforts and financial backing, the Fall River Railroad Company began construction in 1844, and was completed the following year. With the creation of the Fall River and Old Colony Railroad in 1854, yet another venture which was due in large part to Borden’s backing, the Fall River area (and Borden) achieved an important goal – a direct rail line to Boston. Not surprisingly, Borden served on the new line’s board of directors for several years during the 1850’s.

Stockbridge and Pittsfield Railroad, Massachusetts

Chartered in 1847, construction began in 1848, and the entire twenty-two miles of track running from Great Barrington to Pittsfield opened on January lst, 1850. The Housatonic Company took a perpetual lease of the railroad in the same month in exchange for a seven percent rent based upon the total construction cost of about $450.000. The Housatonic Company operated the line successfully for a number of years, consistently meeting its annual rent charge without difficulty.